|

| AUGUST THE FOURTEENTH -TWO THOUSAND ELEVEN |

|

|

|

|

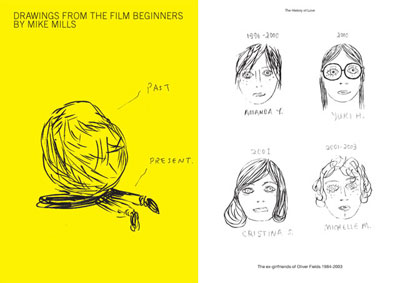

ESSAYS Responses to Mike Mills' Beginners and Miranda July's The Future Posted: 8/14/11 Mike Mills brings us his sadness; Miranda July, her wildness. The directors, who married in 2009 after meeting while promoting their 2005 debut films, his Thumbsucker, her Me and You and Everyone We Know, epitomize the power indie couple. In addition to writing the screenplays for their films, they both maintain separate artistic practices, his background in graffiti/graphic design/illustration, hers in all things performance/literary/sculptural. Of course, every news outlet from the Times to NPR to Philadelphia Weekly has reviewed their coinciding sophomore film efforts, and to add a voice to that chorus seems redundant. Their fans are super-fans, their critics react with disgust. The audience for existentialist talking pets is divided. What interests me, however, is considering these films in conversation with one another. There is an aching, bourgeois malaise that both Mills and July make palpable, through characters that may be extensions of themselves--pensive, panicked, confused in their relationships and life trajectories. Through his autobiographical narrative and her performative gestures, in nonlinear scenes, and traditional storytelling, the real meat of the films happens in the places where their connected lives, creative and personal, feel transparent and vulnerable on screen. These studio dilemmas feel far more urgent than the generic, expected romantic subplots. July and Mills must play this game: Double Solitaire, a title applied to a recent exhibition of married surrealist painters Yves Tanguy and Kay Sage. Like Mills and July, Tanguy and Sage claim to work in separate studios and avoid artistic collaboration. Yet for both couples, their works reflect a natural synchronicity, depict eerie visual coincidences, and indicate a certain “he says, she says” interpretation of shared perspectives Double Solitaire implies that the two play the same creative game, with a different deck of cards, silently strategizing beside one another with an intense but subtle parallel energy between their projects.  PHOTO: http://www.aiga.org/the-designer-as-filmmaker-an-interview-with-mike-mills/ Cover of the book Drawings from the Film Beginners (Damiani) by Mike Mills; and from the section The History of Love, a drawing titled “The ex-girlfriends of Oliver Fields 1984-2003.” In Beginners, Mills is fictionalized as Oliver (played by Ewan McGregor) in a semi-autobiographical story about mourning the death of his 75-year-old gay father. The real-life Mills Sr., played in the film by Christopher Plummer, came out and proud only in the last five years of his life. The event forces Oliver to confront his parents’ farce of a marriage and his own depressive, commitment-phobic record with women. In the film, Oliver works a brightly colored graphic-design firm, where he ceaselessly strives to infuse his project-based work with dark, self-obsessed narrative. His drawings are sweet, naive: fireworks, portraits of ex-flames, pithy statements. He, like Mills, draws in order situate his personal pain within a larger, wholly indifferent universe. Later, in a cathartic reclamation of his youth, Oliver defaces the clean, white expanse of an empty billboard. He climbs the tall billboard only to write graffiti with hesitance and middle-aged defeat. He scrawls a sentence of personal melancholy over the indifferent LA landscape: YOU MAKE ME LAUGH BUT IT’S NOT FUNNY. Mills’ former endeavors translate strangely to film; the intellectual graffiti mark seems more witty album liner note than urban sign. The scene is hilarious, and poignant--the tag seems to indicate Oliver’s deep nostalgia for an easier time of his youth, when he just knew less. Later, back at the office, he illustrates the history of sadness in shaky drawings awkwardly bound in an accordion book, spilling out like intestines, tragic like a funeral dirge. It presumes to be touching and ironic, but is ultimately rejected by a bored, upbeat indie rock band. Both moments in the film illustrate Oliver’s urgency to emote--to reach out to an apathetic audience and demand some feeling. In The Future, July, playing some approximation of herself as Sophie, makes the inconsequential decision to adopt a stray, anemic cat with her live-in boyfriend, Jason. This humorously results in their serious life reflection and individual crises--all of a sudden, the prospect of adopting an old cat makes their next fifteen years fly by, and seem wasted. Confronting her own personal and professional disappointments, Sophie willfully unravels herself and their life together. It’s devastating, but comically so. Bizarre antics, frozen time, and a talking moon do the rest. Sophie, a dancer turned dance instructor, also initiates and quickly abandons an online project she calls 30 Days, 30 Dances. It is July’s artistic practice fictionalized: her conceptual interest in stranger contact, amateur performance, and failure all there, on-screen, exposed.  PHOTO: http://cinema-scope.com/wordpress/tag/miranda-july/ Still from The Future In fact, July indicated that the film’s narrative began as an earlier live-performance project, which she recreates at the climax. It is a dance with her “shirtie,” an XXL t-shirt-made-security-blanket that Sophie clings to and alternately rejects, a prop that is authentically July. She animates shirtie, stretching her legs into its armholes, elegantly draping it up her body over her head until it envelops her person--shirtie and Sophie uniting, like Peter Pan meeting his shadow. In embracing shirtie, she finally faces herself: her own shortcomings and life re-course; the moment seemingly compensates for the 30 choreographed movements she failed to create in her online project. Her body floats, headless and heartbeat-ing, around the spare, suburban bedroom in the undulating, unitard t-shirt. She is sexless and haunting, and recoils when her sleazy lover enters to watch. It is cringe-inducing and beautiful--the best of July, without any pretense or hipness or remarkable haircuts. In these scenes, the characters or surrogates for Mills and July, confront fears and doubts inherent to their artistic practices. Thoughts like “Will anyone ever see this/find meaning?” feel pantomimed in front of us. And artists will find that it is not hard to relate, translating one’s own studio practice--amateur gesture, lost meaning, misinterpreted sentiment-- into a self-indulgent, indie feature-length. In their self-indulgence, though, Mills and July access remarkably broad territory. Recently, the filmmakers have addressed their interests in creating space. Speaking with Richard Lim of the NY Times, Mills asserts that he uses film as a way to make a space for sadness. His concerns stem from growing up in “not just a family but a town and a culture where sadness is something you’re taught to feel shame about. You end up chronically desiring what can be a very sentimental idea of love and connection.” July investigates a more internal void. In an interview with David Louis Zuckerman of the Film Society at Lincoln Center, she says, “you can have an existential crisis, where you can’t do the thing that you set out to do, and so you look for the first opportunity to break up with yourself and get away from the identity you had planned.” He asks, What is real, does it hurt? / (She opens a window, lets out a scream.) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||